- Home

- Camp Wolters

- A Model Soldier

- Camera Trip Through Camp Wolters

- Camp Wolters Longhorn

- Camp Wolters Ephemera

- Camp Wolters Guide

- Camp Wolters IRTC

- Camp Wolters Postcards

- Camp Wolters Unit Photos

- Christmas Menu

- Present Site of Camp

- Southwestern Bell Booklet

- Camp Wolters Souvenir Book

- IRTC Doughboy

- Soldier - Billy S. West

- Soldier Artist

- Soldier's Letters

- Soldier's Photos

- Fort Wolters

- United States Primary Helicopter/School

- Flight Training

- ORWAC Class 68-24

- WORWAC Class 67-5

- Training Aircraft

- Stagefields and Heliports

- Southern Airways of Texas

- USAPHS Commandants

- Battery D, 4th Missile BN 562nd Arty

- 328th U.S. Army Band

- Det. 20, 16th Weather Squadron

- Guide and Directory

- Crash Rescue Map

- Dave Rittman Photos

- Fort Wolters Photo Gallery

- Fort Wolters Ephemera

- Wolters Air Force Base

- Fort Wolters Main Gate

- Around Mineral Wells

- Texas Forts Trail

- Vietnam

- Sitemap

- Links

- About the Site

- What's New

| The H-23 helicopter was the military version of the Hiller UH-12 helicopter, manufactured by the Hiller Aircraft Company of Palo Alto, California. There were over 2,000 helicopters (military and civilian) of this series produced before production ended and there is still a healthy after-market for re-manufactured examples of this study workhorse. | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| TH-55-1520-206-10 was the Operator's Manual which covered the relevant flight characteristics and technical details of the OH-23D, F and G models. To view the complete "dash-10" manual, Click on the Image Cover to the leftWhile the Operator's Manual described how to operate the OH-23 and its systems, it was more useful for rated pilots, and student pilots who were learning to fly would more frequently refer to the "Primary Flight Training Manual" to reinforce the airmanship lessons they received from their Instructor Pilots.

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

The variants used by the U.S. Army were as follows:

In October, 1963, an OH-23G piloted by CPT. B. G. Leach set up six international helicopter speed records in classes E-1-b and class E-1-C, ranging up to 123.695 mph over a 3 kilometer course.The different versions of the H-23 were used in a variety of roles by the U.S. Army, serving as a utility, observation and MedEvac roles during the Korean War. It was later used for the primary training of U.S. Army helicopter pilots at Fort Wolters, as well as serving as an armed observation helicopter in the earlier part of the Vietnam war.The medevac version of the OH-23 carried two external skid-mounted litters or pods. The Raven could be armed with twin M37C .30 Caliber machine guns on the XMI armament subsystem or twin M60C 7.62 mm machine guns on the M2 armament subsystem. The XM76 sighting system was used for sighting the guns. In Vietnam the OH-23 was replaced by the Hughes OH-6A Cayuse.

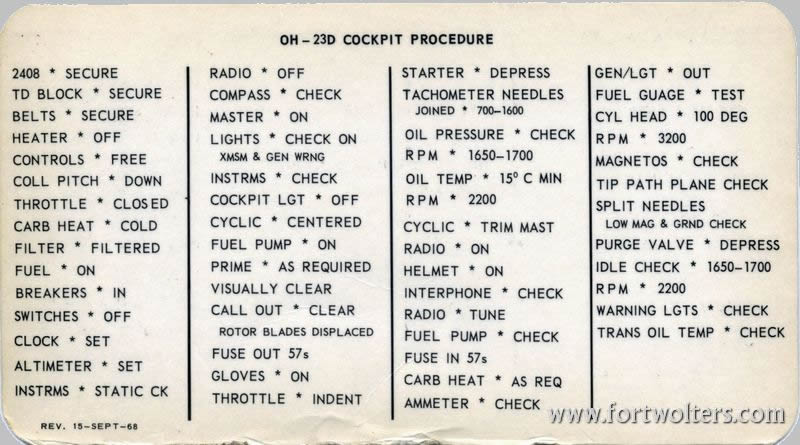

The "OH-23D Cockpit Procedure" card was on laminated stock and gave the instructions on how to get the aircraft started. Initially a copy was issued to each student pilot but were frequently lost or misplaced. Additional copies could be purchased at the Bookstore on the post for a nominal amount.

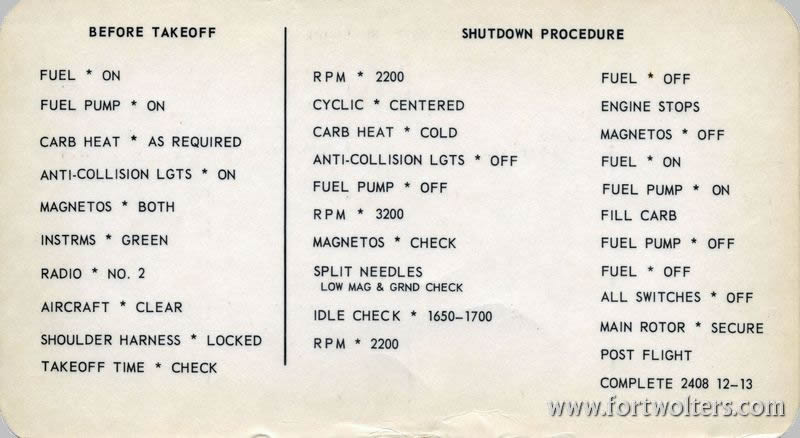

On the flip side of the card was the "Before Takeoff" procedure and the "Shutdown Procedure." The "Before Takeoff" procedure was used after the OH-23 was cranked, warmed-up and all of the cockpit checks had been made. After clearing the aircraft visually, the engine was throttled up to 3200 rpm, collective added to bring it light on the skids and then up to a 3 foot hover. Another visual check and the OH-23 was hovered down the takeoff lane to the takeoff panel. The "Shutdown Procedure" was followed at the end of the period of flying. It was important to leave the aircraft in a uniform state for the next student pilot - the more so because the same aircraft could be flown in the morning, afternoon and even at night on the same day. | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Reminisces of the OH-23 at Fort Wolters The OH-23 Raven aircraft was a good, honest helicopter – one that was equally adept at performing reconnaissance, observation, medical evacuation and training roles. In all of these functions it served the U.S. Army well and helped trained many thousands of student aviators, imparting the skills they would later need in other aircraft and in situations in peace and war. All aircraft, including helicopters, have their own unique “personalities.” These personalities are often a meld of their flying characteristics, mechanical reliability, and are tempered by memories formed by actually flying these aircraft. To me the OH-23 was a trusted friend, always predictable and reliable. Metaphorically, the ’23 was like a pair of old slippers, used periodically, but always appreciated for their utility and comfort. I have nothing but good memories of the OH-23 Raven. For much of its time at Fort Wolters, it was the only aircraft used for training. Later the ever increasing need for helicopter pilots in Vietnam, plus the actual diversion of some of its numbers to Vietnam, meant that the training fleet was later supplemented by the Hughes TH-55A and the Bell OH-13 aircraft. I don’t think that any rationale was applied to which students were assigned to which type trainer, but I personally was very glad to be assigned to the OH-23 flights. Gosh, the TH-55s were tiny! With the aid of the laminated checklists, and the orange “Primary Flight Training Manual,” plus the guidance of our Instructor Pilots, the pre-flight and cockpit procedures were quickly learned. Even in winter, when exposed to the cold and damp of the main heliports the OH-23’s usually started easily – due of course to the fine maintenance they received from the Southern Airway mechanics. If a recalcitrant aircraft wouldn’t start, a passing Southern Airways jeep could often be waved down for help. Failing this, at different locations there were phone booths where replacement aircraft could be requested and quickly assigned. Or, if battery power was available, the radio could be used to contact maintenance control on an assigned radio frequency. I do remember trying to bring the OH-23 to an initial hover once only to find I had fastened my seat belt around the collective control , which of course severely restricted its movement. I was thankful to set down and correct my careless mistake. Hovering, once learned, was fairly easy in the OH-23. Sometimes the collective control felt “heavy” when hovering and this was a characteristic of the Hiller “Roto-matic” rotor design. A sharp “pop’ on the collective freed the rotor mechanism and the collective felt light again. The OH-23 had no hydraulic controls, which greatly simplified maintenance and also flying controls. On top of the cyclic was a “pagoda” type control known as the cyclic trim switch. The purpose of this control was to trim out cyclic control pressures making the aircraft easier to fly. Returning to Wolters after Vietnam I had a staff job and flew the OH-23 only to retain proficiency - and of course to receive flight pay. Our enlisted driver was a draftee, due to be discharged soon, who approached me and asked if I could take him up for a flight in a helicopter. In his two years in the service, including duty in Vietnam, he had never once flown in a chopper. I told him I would be happy to take him up for a flight the next time I scheduled an aircraft. A couple of weeks later I scheduled a OH-23 and drove down to the Main Heliport with the driver. The weather showed to be southerly winds with intermittent rain showers – no problem. I noticed in the aircraft’s 2408 form that a previous problem with the cyclic trim had been cleared, so I cranked the OH-23 and hovered down to a takeoff panel in east traffic. After takeoff we swung to the north and I could see that the driver was smiling and obviously enjoying himself. Clear of most training traffic, I split the needles and entered a practice autorotation, which did not faze my passenger at all – same smile on his face. When I added power and started climbing I noticed that rain was sweeping in and the clouds were turning very dark. Simultaneously with this observation was the realization the aircraft had some very strong trim forces and was becoming difficult to handle. In the OH-23 the cyclic trim was controlled by one of four 24-volt motors, which controlled longitudinal and lateral trim forces. There was also a cyclic trim circuit button on the lower part of the panel but it would just re-trip when I tried to reset it. The wind had turned to the north and the rain increased in intensity. My passenger was still grinning and totally appeared totally unconcerned. Because of the trim forces and buffeting winds, I got on the intercom, explained the situation and asked him to get on the cyclic with me and to follow my control inputs. He received my communication with a broader smile and just sat there. I repeated my request and he smiled even more – which was starting to annoy me. I was to get no help and it was a difficult struggle to return to the Main Heliport and land. Hovering was difficult and so I set down the aircraft and scooted along the ground. Later at the office our driver told everyone what a great pilot I was and how much fun the flight had been. I asked him why he hadn’t responded to my request for aid and he said he thought I was just trying to “mess around” and that I was just pretending. My humor returned quickly, he obviously had trusted in me implicitly and I thought that he would retain a good memory of his only helicopter flight in the Army. He later told me that he wished he had taken his camera with him and would there be the possibility of another ride before his discharge. I smiled and referred him to another rated pilot in the office. Another memory I have of the OH-23 is the time I thought I would like to see how high one would climb. The Dash-10 manual didn’t specifically give a service ceiling but other sources gave it a service ceiling of 15,200 feet. I had never flown that high in a helicopter before and I knew that we were expected to be on oxygen (which the ’23 didn’t have) above 14,000 feet. Anyway, it was a cold, clear winter’s day and I needed some cross-country time for my flight minimums. I took off from the Main Heliport and headed off towards Wichita Falls. The ’23 flew strongly and the cold, dense air certainly helped support the rotors. Well clear of student training traffic, I started climbing and just kept going upwards. After a period I sensed that the engine was running a little rough so I adjusted the carburetor heat lever and it smoothed out. I had to do this a few more times, but eventually the carb heat was fully on yet the engine was really running rough and the Carburetor Air Temperature Gage had dropped below the yellow range (0 to 31degrees Centigrade). Ice was certainly forming in the venturi of the carburetor and I reluctantly had to give up with altimeter reading 9700 feet. I came down slowly to about 7000 feet and then split the needles to descend in an autorotation until I reached a more normal altitude. I told some of the other OH-23 rated pilots in the office of the altitude I had reached, and invariably in true Army Aviator fashion they all claimed to have greatly exceeded my paltry height – some many times. With hundreds of OH-23s in the training fleet at Fort Wolters, invariably there were differences in performance between the individual aircraft - some of the ‘23s were “strong” and some weren’t. The Southern Airway mechanics did a great job of rebuilding worn engines and returning them to service in their engine shop. One hot summer’s day I was scheduled to fly the first period dual with my instructor. As I waited, a student officer from our class came in and asked if he could hitch a ride with us to the Stagefield. He had been delayed and had missed the bus with the non-flying students. No problem, the three of us piled in our assigned aircraft, got it cranked and hovered to the takeoff panel. Well, the combination of a high density altitude, three in the cabin, and an old worn out 1957 model OH-23 just wouldn’t allow us to take-off. Just beyond the takeoff panel there was a short fence at the perimeter of the Downing heliport, but our aircraft refused to fly and just couldn’t clear the measly 4 foot impediment. Three times we tried and failed, it was now a matter of saving face and proving that it could be done if the proper pilot technique was used. “Let me show you both how we did it in Vietnam,” our Instructor said as took over the controls. We backed up a good 150 feet and then bounced across the tarmac as he attempted a running takeoff to get transitional lift. Well we did fly, only just though; I think we cleared the fence with about a foot to spare. At the Stagefield we dropped off our passenger and the aircraft flew better, but climbed slowly and certainly was ready for an engine rebuild I suppose every person who flew the OH-23, has many stories to tell about this sturdy, reliable aircraft. Many examples flew in combat and did yeoman service in Vietnam. I think history will record that as a primary trainer at Fort Wolters it served the Army in its most important role.

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||